Could community health workers reduce US health inequity?

Covid-19 may have exposed the legacy of decades of healthcare discrimination in the US, but the idea that race adversely affects health outcomes is a shared reality for community health workers such as Cheryl Garfield

No one is perhaps better placed than a community health worker (CHW) to understand the merits of a healthcare system that acknowledges it exists to serve a remarkable diversity of communities and needs without discrimination. The notion of healthcare equity seems like a given in 2021, but statistics revealing the disparity in healthcare outcomes across different racial and ethnic groups indicate how much work still needs to be done to deliver non-discriminatory healthcare and services.

According to the US government agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), black adults under the age of 50 are twice as likely to die of heart disease as white adults. The Covid-19 pandemic brought this divide into stark relief with Hispanic Californians between the ages of 50 and 64 dying of the disease at more than five times the rate of white people of the same age. That is but one shocking statistic of many showing how the pandemic has adversely affected communities of colour across the US.

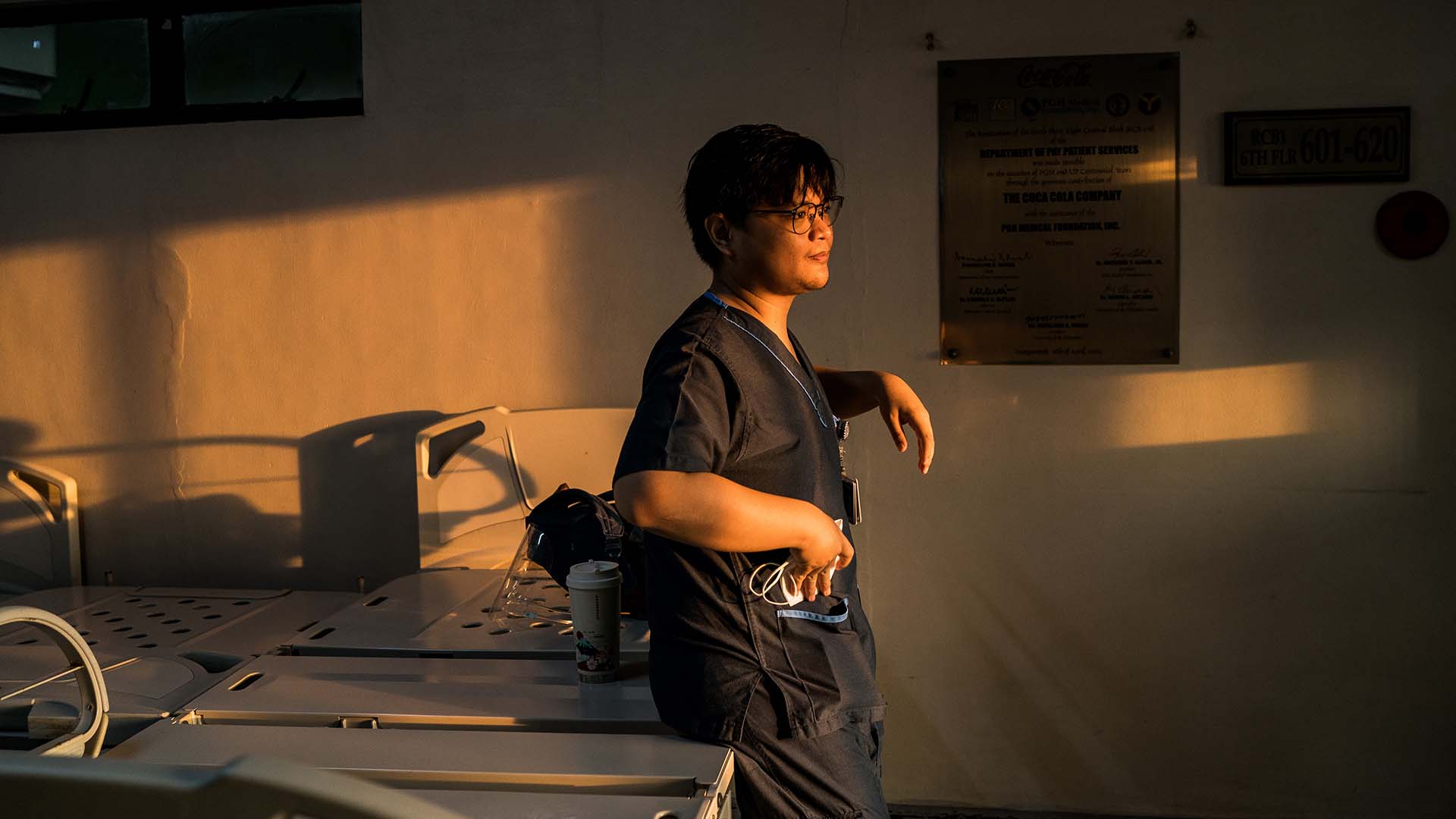

Cheryl Garfield is a black woman who has lived in Philadelphia for all but two years of her life. The 52-year-old grandmother has endured personal trauma and strife and manages significant health issues — all while championing the health of the people in her community, whom she serves as a CHW.

“We’re working to make everything good for all communities,” says Garfield from her office at the Penn Center for community health workers, part of Penn Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania’s health system, where she has worked for the last eight-and-a-half years and is a lead community health worker.

“We’re very hands-on and we build trust with our patients, often times patients see us as a family member. We connect with them more because we’re from the community, and we have some of the shared life experiences that they have,” she explains. Her point of view offers deft analysis of why culturally competent care — healthcare that meets the social, cultural and linguistic needs of patients — works so well in reaching members of the community, including people of colour, who might be out of sight or marginalised by mainstream healthcare providers.

“Patients tell us things that they won’t tell their healthcare providers, social workers, or case managers at the doctors in the clinic or at the hospital. They don’t know that a patient is afraid to say that their electric is off, because if they do, there might be repercussions like being reported to the Department of Human Services (DHS) and having their children removed from the home.”

“They’ll tell us things that they won’t tell their healthcare providers or the doctors in the clinic or at the hospital. The doctors don’t know that a patient is afraid to say that their electric is off, because if they do, they’re scared that the social worker will come in and take their children. I call it the ‘White Coat Syndrome’.”

While CHWs have existed in the US for decades, their number has grown significantly since 2010, when the role of CHW was included as a health profession in the US Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. They are now recognised as a vital link in the US public health and healthcare system, especially when it comes to addressing the social determinants of health among underserved populations in urban and even remote rural areas, and forging connections between public services and the community.

While CHWs have existed in the US for decades, their number has grown significantly since 2010, when the role of CHW was included as a health profession in the US Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. They are now recognised as a vital link in the US public health and healthcare system, especially when it comes to addressing the social determinants of health among historically underserved populations in urban and even remote rural areas, and forging connections between public services and the community.

CHWs do vital work across communities who face health inequities, such as providing social support, advocacy, navigation and health coaching while working to put individuals in touch with a range of essential services from mental health support to drug and alcohol treatment.

The success of CHWs lies in their unique ability to act as a bridge between underserved communities and institutional healthcare providers in ways that might break down barriers across US public sector provision for racial and ethnic minorities.

In 2021, President Biden proposed employing 100,000 more community-based workers as part of the American Rescue Plan Act, his $1.9tn economic stimulus package to combat the Covid-19 pandemic. But for Garfield and her colleagues, even more fundamental changes are needed, not least when it comes to addressing the all-pervasive issue of race. According to the US Census Bureau in 2014, 37.9 per cent of the US population was identified to be racial or ethnic minorities; this is significant given that race is perhaps the most substantial cause of health disparities, including higher rates of chronic disease and premature death than the white population. The White House accepted the findings of the CDC when it revealed the ways in which Covid-19 had disproportionately affected people of colour, saying it is the result of “lasting systemic racism” in the US healthcare system. It is a situation that Cheryl Garfield and other CHWs across the US are working to change.

In Philadelphia, as in so many American cities, life experiences and circumstance can often act as barriers to healthcare and social welfare, especially among racial and ethnic minorities. These include unemployment, poverty, incarceration, exposure to harmful environmental factors, illiteracy and low educational attainment, addiction and, not surprisingly, systemic racial discrimination. Garfield and her fellow CHWs know that the key to breaking down such barriers is to understand them.

“When I work with a patient, I want to get to know them as a whole person. I start off by asking them, ‘Tell me about yourself’, because oftentimes people don’t associate things that have happened to them, maybe even a trauma in their childhood, with the way their health is today,” she explains, describing the need for culturally competent care.

“People and organisations are now implementing programmes to tackle racism and social injustice,” she says. “We have groups that mix managers and health leaders with CHWs and community leaders to develop policies and make changes across the whole health system.”

Organisations are waking up to the potential for embedded community outreach professionals to bring lasting and effective change. When Garfield was hired by Penn’s CHW Center in 2013, she was one of only five CHWs in the organisation; eight years later the Center has 65 employees, and is about to launch a mentoring programme through which CHWs mentor doctors and senior healthcare executives. For two weeks each year, Garfield also teaches third- and fourth-year medical students about what it is to be a CHW, the aim being to equip them with the necessary insight and empathy to move beyond ideas of health and sickness towards care that addresses the needs of the whole person.

“They pick up patients, they follow them and they stay with them, just like I would,” she explains. “They’re given the opportunity to learn about the people that they will be serving in the community and that helps to shape the next generation of healthcare providers. It brings awareness and lets them see people’s humanity.”

When asked what keeps her going despite the challenges she faces, Garfield says that she is driven by her passion to help those in need.

“My motto is “Each One, Teach One”. If I teach one person, they can teach somebody else, and that way everyone will end up with the knowledge to do what needs to be done to change the world.”

The Penn Center for Community Health Workers is partially supported through a grant from the Johnson & Johnson Foundation.